era-defining

innovation

In the previous two parts of this project, we’ve made a case for a 21st-century sound that’s innovative and influential. However, the question that we are concerned with is whether these innovations are sufficient to define a new era in popular music, as rock did in the 1960s. To frame our consideration of this question historically, we go back to the first three decades of the last century. Our objective is to experience the changes in the musical environment over a similar timespan, then use what we experienced to compare musical innovation during that time with innovation in the early years of this century.

To experience innovation in popular music during the early decades of the 20th century, we contrast two groups of songs. The first group features four of the most popular songs of the 1900s. All four songs were the equivalent of #1 hits—three decades before Billboard published its first “hit parade” chart. Three of them are waltz songs, the most popular song genre around the turn of the century. “Grand Old Rag” is a “march” song—a song supported with an accompaniment with a march rhythm. Bands led by John Philip Sousa and others were among the most popular musical entertainments during this time, so it’s not surprising that the influence of band music surfaced occasionally in popular song.

The second group of recordings date from the late 1920s. Collectively, they demonstrate key innovations in the popular music of the 1920s. The earliest, Fletcher Henderson’s “Sugar Foot Stomp,” exemplifies the sound of a “hot jazz” dance orchestra: a cutting-edge sound ca. 1925. The remaining six recordings — all but one on film — evidence the assimilation of some or even all of these these innovations into more mainstream popular song. We hear both vocal and instrumental performances of the songs.

two generations of popular music

The playlist above overlaps with the musical excerpts on the explanatory videos below. However, it is incomplete in two ways. One song is missing altogether: “You’re Just Another Memory.” The other is that the playlist includes versions of several song that differ from the film versions. The complete YouTube videos for these tracks are included at the very end of this part.

recording in the early 20th century

Both sets of recordings represent important milestones in the history of sound recording. The recordings from the 1900s are among the first commercial recordings. They were recorded acoustically. The recordings from the late 1920s benefited from a technological breakthrough that dramatically improved recording quality almost overnight.

acoustic recording

Commercial recordings had been available for more than a decade when Billy Murray recorded “Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis.” Still, the acoustic recording process in use at the time was primitive: performers gathered around a big cone. The technology at the time was limiting not only in the quality of the recording, but also who could successfully record. Singers with strong voices, like Billy Murray and Al Jolson, were successful, and the narrow range of frequencies available in acoustic recording meant that low bass and high treble instruments did not record well.

electrical recording

Audio recording improved almost overnight in 1925, with the emergence of electrical technology. This made possible higher quality recordings, network radio, amplification in live performance, and—two years later—talking films. Electrical recording not only improved sound quality and made it more available, it also opened up opportunities for a broader range of performers. By way of example, we’ll hear a young Bing Crosby singing in a more laid back style, which would not have recorded well earlier in the decade.

A photo from NBC’s first network radio broadcast. It features a dance orchestra. The microphone used in the broadcast is directly under the sousaphone.

It’s hard to imagine popular songs that are more different from the tracks by Drake et al. than the three waltz songs. The more recent tracks have minimal melody. By contrast, these songs are all about melody; it is the element that most clearly differentiates one song from another. We can experience this by listening to the chorus of all three songs back to back.

One reason for the focus on melody in these songs is the nature of the music business at the time. As we have heard, recording was primitive and records and phonographs to play them were expensive. Instead, the primary method of disseminating popular song was through sheet music. The target audience was amateur musicians who learned the songs by reading the music. For that reason, the sheet music version of a song was supposed to be relatively simple to play (although it wasn’t always the case).

popular songs from the 1900s

However, the main reason is that waltz songs belonged musically to the previous century. They were the last iteration of melody-oriented popular song that catered to an American middle class audience. Their most novel feature was the waltz rhythm, although the songs were not for social dancing. They contained no trace of the syncopated music that was bubbling under around the turn of the century.

the waltz song

Key features of the style include:

A generic, variable accompaniment. The sheet music version of the song offered a piano accompaniment appropriate for skilled amateurs. Professional recordings, like the one presented below, used larger ensembles made up mainly of wind instruments.

A waltz rhythm: it’s straightforward, and it continues throughout the song. .

A melody that consists of a series of phrases punctuated at regular intervals. The rhythm of the melody is simple and unsyncopated. It does not resemble the rhythm of everyday speech — we don’t say the lyrics in the same rhythm that we sing them.

Harmonies that draw from a slightly enhanced version of a familiar musical language

“Grand Old Rag” is more up to date. It features a march rhythm instead of a waltz rhythm underneath the melody, and the rhythm of the melody is more varied. It occasionally includes phrases that make use of the signature rhythm of the cakewalk (e.g., “high-FLY-ing flag”)—the cakewalk gently introduced this simple African-derived syncopation into popular music during the 1890s.

a march song

This video includes the choruses of the four songs. The three waltz songs are heard in chronological order.

toward a new kind of popular music

These four songs from the 1900s comprise our reference point for assessing the new music of the 1920s. It is against these songs that we’ll assess the nature and the degree of innovation heard in this new hybrid music. The new sounds that we’ll hear were the result of the comprehensive assimilation of African-derived musical features into the prevailing musical language. They were absorbed progressively, against fierce resistance, over a relatively short timespan: only 20 years separate the two groups of songs. We hear — and see — the profound transformation of popular music directly below.

Popular songs and dance music from the late 1920s

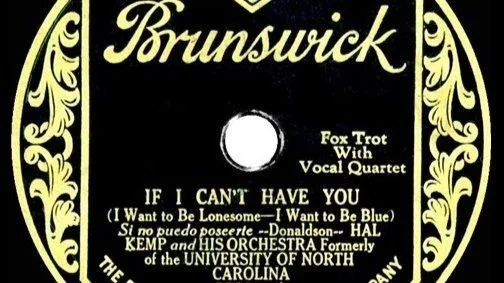

People dancing the fox trot to a 1928 hit song. Almost every song from the 1920s was a fox trot—or at least labeled as one.

This short video highlights one of the key differences between the songs from the two generations. The songs of the 1900s were not for social dancing, even though the melodies were supported by a waltz rhythm. By contrast, the songs of the 1920s were fox trots: appropriate for singing and social dancing. Most of the recordings that you’ll hear shortly were performed by dance orchestras. In these recordings, the vocal segment of a recording was typically only a single chorus—less than a third of the total length of the recording.

Notice “Fox Trot With Vocal Quartet” on the label.

We can understand the fusion of song and dance as the first iteration of a pattern that recurred throughout the 20th century. Every generation of 20th-century popular music began with a new dance fad — the fox trot in the 1910s, swing in the 1930s, rock and roll in the 1950s, and disco/funk in the 1970s — that was defined in large part by its distinctive rhythmic template.

The rhythmic template soon became the foundation for the majority of the music of the era. That’s certainly the case in the vocal (or at least singable) songs heard below. The recurring appeal of danceable music was an indication of the growing appeal of the African-inspired rhythms of this new hybrid musical tradition.

A new integrated musical tradition

The popular music of the late 1920s was the first full iteration of the integrated African/European tradition. During this time, we can describe the relationship between the two cultures this way: the European tradition determined what was performed; the African-American tradition determined how the music would be performed.

The evolutionary dialectic within their interaction was a continuing back-and-forth process of adaptation and reinterpretation between the two. African-Americans took what they heard and filtered it through their own sensibility. White musicians who were drawn to these adaptations would then bring what they heard into their own playing. This process was at the heart of evolutionary change within the tradition.

These four recordings outline the adaptation / reinterpretation process during the early years of the European/African tradition. .

These four versions of “St. Louis Blues” encapsulate the process by which these two disparate musical cultures blended into a distinctly new kind of music. W. C. Handy, the composer of this song and several other blues numbers, took the sound and style of a march — Handy was a bandmaster, after all — and colored the harmony with the blue notes of the melody. This in turn changed the function of the chords from how they were used in the waltz songs and other conventional music. This was, like the syncopations in Joplin’s rags, a black take on white music.

The first recording features a band led by Charles Prince performing an extremely faithful arrangement of the published version of Handy’s song. It uses blues form in the first and last sections — the middle section is a tango— but offers no hint of the blues style that we hear in the second recording.

In 1925, the classic blues singer Bessie Smith and trumpeter Louis Armstrong infused their performance with the rhythm liberty and heightened that we continue to associate with blues style. This was in effect a further adaptation of Handy’s initial take on the blues.